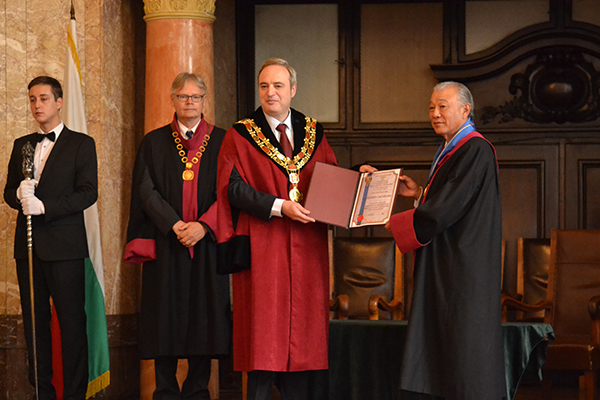

At a solemn ceremony held at the Aula magna of the University Professor Dr Habil Anastas Gerdzhikov, Rector of Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, conferred a Doctor honoris causa degree of the University of Sofia “St. Kliment Ohridski” on Mr Yohei Sasakawa, Chairperson of The Nippon Foundation.

The proposal for the conferral of the honorary degree by the oldest and most prestigious academic institution in this country came from the Faculty of Classical and Contemporary Philology of the University.

The ceremony was attended by HE Mr Takashi Koizumi, the Ambassador of Japan to this country, guests from Japan, faculty and students from Sofia University.

The ceremony was opened by Professor Dr Habil Alexander Fedotov, Director of the Center for Eastern Languages and Studies at Sofia University, who introduced Yohei Sasakawa to the audience. Professor Fedotov said that Mr Sasakawa was a person of remarkable contributions to both the global development of the humanities and the financial sponsoring of culture, the level of teaching at Sofia University included.

“The Nippon Foundation presided by Mr Yohei Sasakawa, also known as the Sasakawa Foundation, awards scholarships to Ph D students in 69 universities in more than 45 countries worldwide. Such scholarships have been awarded to Sofia University Ph D students since 1993. Ever since the Sasakawa program has been consistently very successful. Its winners include more than a hundred Bulgarian Ph D students. They have utilized the funding in studying and conducting research work abroad. In 2016 five Ph D students from Sofia University won the scholarship,” Professor Fedotov added. He also said that apart from expressing the gratitude on the part of our Alma mater’s Ph D students, the honorary degree took into account Yohei Sasakawa’s considerable contribution to a number of noble causes including the struggle for the complete eradication of leprosy as a disease and the accompanying social discrimination of both its victims and reconvalescents all round the world which particularly stands out. Mr Sasakawa’s contributions were also confirmed by the fact that he was appointed WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination, Professor Fedotow pointed out.

Yohei Sasakawa received his degree in Tokyo, from Meiji University’s School of Political Science and Economics. Since 1952 he has been on the Board of Directors of the Nippon Foundation; since 1989 he has been its President, and since 2005 its Chairperson. He served as a special envoy of the government of Japan in the national reconciliation process in Myanmar.

Yohei Sasakawa holds many prizes, amongst which the Special Award of the World Maritime University (Sweden), the Rule of Law Award of the International Bar Association, the International Gandhi Award. He holds a Doctor honoris causa degree from a number of universities such as York, Malay, Bucharest; he is an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences.

Professor Dr Habil Anastas Gerdzhikov, Rector of Sofia University, conferred the prestigious award on Mr Yohei Sasakawa. Mr Sasakawa expressed his gratitude for the honor bestowed on him and said how deeply touched he was of being given the opportunity to talk in front of a Sofia University audience about the efforts he had made over the years to eliminate leprosy. The audience had the opportunity to watch a short video dedicated to the noble cause of Yohei Sasakawa. The video presented the real life of those who had suffered or were suffering from leprosy: the latter, once classed as an incurable disease, a curse and a punishment from God, scared and repulsed people for centuries.

In his academic lecture "Victory on Two Fronts: The Elimination of Leprosy as a Disease and as a Stigma" Mr Sasakawa observed that it was due to the progress of efficient treatment that leprosy can be cured today. The Nippon Foundation has significantly contributed to the free and accessible treatment of the disease worldwide. He recounted how once the medicine had been made accessible, they had expected immediate results to come out. However, they had faced some unexpected challenges. Many of the patients did not know how to take the pills since they were familiar with their traditional medicine only. With some African tribes, who respected the tradition of food being shared equally amongst the members of the community, the same thing happened with the medicine that made the latter respectively ineffective. In other cases, the patients did not turn up regularly to receive the treatment although it was free of charge. They claimed they had no symptoms of the disease although they were in fact in its initial stages, or they were afraid of being ostracized by the community they lived in as lepers.

Thus, very soon it became clear that the idea of solely popularizing the medicine that was free of charge was not sufficiently effective. It was necessary to get familiarized with the local habits, traditions and culture. To achieve more positive results the Nippon Foundation launched joint activities with the national ministries of health, medical specialists and NGO representatives on the spot. Thanks to their joint efforts many patients have fully recovered and the number of those who contracted the disease has significantly fallen in many of the leprosy-ridden countries.

In spite of these remarkable successes in the treatment of the disease, Yohei Sasakawa remarked that the lives of many patients did not significantly change after their recovery. Even after their full recovery, they continued living in sanatoria.

Being witness to that, it became clear to Sasakawa that it was prematurely optimistic to think that the stigma and the discrimination associated with leprosy could be easily staved off. The label of being a leper would accompany even the reconvalescent patients for the rest of their lives. This was why Yohei Sasakawa turned his attention to the solution of that problem. He presented the struggle with leprosy as a bicycle whose front wheel were the achievements of medicine in the treatment of the disease, whereas the back one was the social success in the elimination of the stigma and discrimination related to the disease. In his words, the way the bicycle cannot move if the two of its wheels are not in motion, the same way people have to unite their efforts to provide a solution to the problem both in its medical and social context.

As far as leprosy was concerned, Yohei Sasakawa turned to the UN for assistance; the latter organization adopted a resolution for the abolition of discrimination against people suffering from leprosy and the members of their families only in 2010, seven years after his first visit. Many of the reconvalescents refused to admit of having a problem, fearing discrimination. However, Sasakawa reached the conclusion that it was only when they themselves became consciously aware of the problem that would make the others think of it, too.

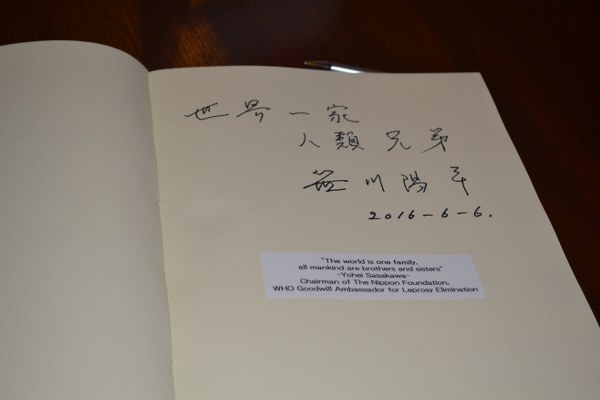

According to Sasakawa what has to be done is to talk of leprosy in real terms because, it is by discussing the problem that we, in fact, think of humanity’s future. Everywhere round the world the disease is referred to as “a negative history” and there are places where it is forgotten or completely eradicated. “At the same time, the history of leprosy is the history how people have contracted it, have stood up to the fact of it and overcome discrimination, even in the most despairing of circumstances. They have lost their identity, their homes, their families, their friends and social lives, and still the road they have embarked on as human beings can be highly instructive when it comes to the strength and tolerance man is capable of. That was a valueless lesson,” Yohei Sasakawa pointed out.

In his words, that was the message that was to be passed on to the next generation – the experience we have with the disease and its social projections. The struggle against the discrimination of the patients should not fall into oblivion in human history. “We must be sure that the voices of the sufferers should be heard by the coming generations. I myself take this as a primary mission and shall continue working for the preservation of the history of leprosy,“ Yohei Sasakawa concluded.